- Cormontan Compositions

- Composition Dates

- Cecilie Dahm Chapter

- Cormontan Music Library

- Published Compositions

- Published Hymns

Cormontan Compositions

Music Composed by Theodora Cormontan (1840-1922)

The table below provides a list of the compositions by Theodora Cormontan uncovered by Michael and Bonnie Jorgensen in 2011. In May of 2015 virtually all of the scores were donated to the National Library of Norway. The Library has scanned the scores and placed them online. To view the scans, go to the National Library of Norway website, find the term “Musikkmanusripter” and do a search for “Theodora Cormontan.”

The list of compositions below is organized in alphabetical order by title. Other information in the table includes:

C#: Not C-sharp, but the Cormontan number. She wrote a three digit number on about three-fourths of the music she composed. This is probably some kind of cataloging number. Theodora likely used a similar system for the music rental service she owned and operated in Arendal, Norway in the 1870’s-1880’s. A consistent correlation exists in compositions where Cormontan indicated both a C# and a date of composition. This enables us to estimate the composition date of the approximately 75% of her compositions that include a C#.

Year: The year indicates the year the composition was written (when known).

Title: The title of her compositions in alphabetical order. Some titles are also translated into English.

Notes: Additional information on the piece.

Opus #: Many of the compositions to which Theodora assigned opus numbers are compositions that were published, though there are numerous exceptions. It appears that opus numbers through the 40’s were published in Europe and opus numbers in the 50’s and beyond were published in the United States.

Instrument: The instrument or instruments for which the piece was composed. Most are for piano solo. There are also some piano/vocal pieces and a few compositions for organ.

The last two columns in the table indicate whether the piece is a published score or in manuscript and unpublished. When published, the publisher is noted in the last column on the right.

Scroll left to right to view table

| C # | Year | Title | Notes | Opus | Instrument | Published Or Manuscript | Publisher |

| C 837 | Adelia Polkette | Piano | M | ||||

| July 1897 | Aftenstemning | – Written in pencil – backside: Naar Solen gaar ned | Voice (melody only) | M | |||

| 1/6 1894 | Aftensalme | – text by Samuel Olsen Bruun – backside: Norwegian Hymn | Piano/Voice | M | |||

| Among Norwegian Mountains [Two Musicpieces] | – same piece as Among the Mountains | Op 3, No. 2 | Piano | M | |||

| Among the Mountains [Two Characteristic Pieces] | – to Mrs. Agathe Grondahl Backer | Op 13, No 2 | Piano | M | |||

| Andante for Organ | Organ | M | |||||

| C 620 | Bagatelle in D major | Op 129 | Piano | M | |||

| 2/3 1876 | Bølgen [The Wave] | – text by Vilhelm Bergsøe – backside: Ved Rokken | Piano/Voice | M | |||

| C 434 | Brownie playing in moonlight, The [Nissen spiller i Maaneskin] | Piano | M | ||||

| 1882 | By, By for Liden [Hush, hush for the little one] | – text by Alvide Prydz – final measure is on the bottom of Eg Veit ei lite gente | Piano/Voice | M | |||

| C 813 | By the Chimney | Piano | M | ||||

| C 808 | By the Sea | Piano | M | ||||

| C630 | Chanson de Bergerette [Song of the Shepherdess] | Op 125 | Piano | M | |||

| C 899 | Chanson sans paroles [Song Without Words] | Op 70, No 2 | Piano | M | |||

| Citizens March | Piano | M | |||||

| C 873 | Dagny [Polka Caprice] | Op 128 | Piano | M | |||

| Dance Idylle | Op 116 | Piano | M | ||||

| Dance of the Flower Girls | – complete score | Piano | M | ||||

| Dance of the Flower Girls | – incomplete score | Piano | M | ||||

| C 436 | Dancing Girl, The [Morceau de Salon] | Piano | M | ||||

| C 445 | 1891 | Dancing Girl, The [No. 1 – Musical Moments] | – Composed in St. Paul, MN | Piano | M | ||

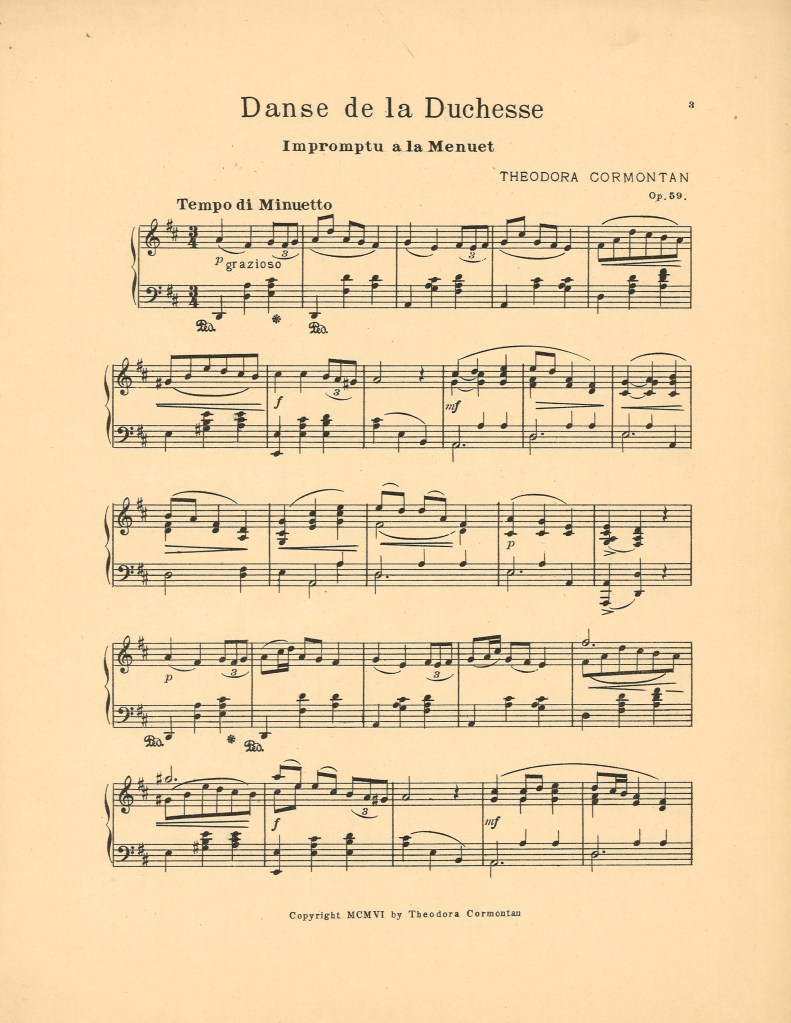

| 1906 | Danse de la Duchesse | – there are three copies of this piece – the Jorgensens kept one copy. The other was donated to the KUBEN museum in Arendal, Norway | Op 59 | Piano | P | Unknown | |

| C 648 | Danse Rustique Norvegienne | Op 76 | Piano | M | |||

| C 800 | Dream of Life | Op 124 | Piano | M | |||

| C 892 | Dreaming by the Hearth [Valse Impromptu] | Piano | M | ||||

| Dream, The [Waltz Caprice] | Op 56 | P | Thompson Music Co., Chicago | ||||

| Dulgt Kjaerlighed [Hidden Love] | – text by Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson | Piano/Voice | M | ||||

| 6/26/1882 | Eg veit ei lite gente [I know a little girl] | – text by Jørgen Moe – backside of Ungbirken – final measure of By By for Liden is on this page | Piano/Voice | M | |||

| C 369 | 1889 | En Damrungslund [In Damrungs Grove] | – backside Vinterbilede incomplete – text by Alberta Eltzholtz | Organ/Voice | M | ||

| C 443 | Evening Sentiments, The | Piano | M | ||||

| C 436 | Fantasia Impromptu | Piano | M | ||||

| C 400 | Fantasia over Serenade de L. Gregh Parais `a la fenêtre | Op 50 | Piano | M | |||

| erased | Fantasia Transcription [over one favorite melody by Halfdan Kjerulf] | Piano | M | ||||

| C 836 | Fantaisie norwégienne | Piano | M | ||||

| C 424 | Fest Marsch | Piano | M | ||||

| C 521 | Fest-Praeludium [I Anledning Gustaf Adolph Festen] | – backside Praeludium til Salmen O tank naar engang | Organ or Piano | M | |||

| Fjeldjom Mountainsong [Sang uden Ord/Song Without Words] | Piano | M | |||||

| Fleur de Printemps [Valsette] | Op 125 | Piano | M | ||||

| C 748 | Fleur Printanière [Spring Flower / Valsette] | Op 83 | Piano | M | |||

| C 809 | Floweret [Romance without Words in A Major] | Op 133 | Piano | M | |||

| Foraars-Længsel [Longing for Spring] | – incomplete score – backside In a Rush | Piano | M |

C 649 | From the Mountains of Norway [Fantasies over Norwegian Folk Melodies] No 1 – Old Folk Song | – No. 2 is called Wedding March. We do have a score with that title but it does not indicate it is part of this set of songs, and its C number is not sequential with these. | Piano | M | |||||

| C 650 | From the Mountains of Norway [Fantasies over Norwegian Folk Melodies] No 3 – Norwegian Folktunes | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 889 | From the Old Time | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 317 | Galop brillante de Concert | Op 20 (?) | Piano | M | |||||

| C 819 | Galop Caprice over Norwegian Folksong | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 403 | Galop Fantasia over Norwegian Folksong | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 817 | Golden Sunbeams | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 816 | Graceful Lady, The | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 883 | Happy Thoughts [Valse Caprice] | Piano | M | ||||||

| Her vil ties, Her vil bies [Here will be silent – Fantasie-Transcription] | – text by H.A. Brorson – there is no text written in this score | Op 38 | Piano | M | |||||

| 1885 | Honor March | – this piece was published by Cormontan from her own publishing company in Arendal in 1885 – this is a manuscript, however | Op 44 | Piano | M | ||||

| C 509 | Hör, hvor de lokke, de klinge [Listen, how they lure, how they resound: vals-arie for tenor and soprano] | – Text by Sylvius–“Sylvius” is the pen name of Hans Jorgen Synnestvedt (1842-1863) | Piano/Vocal Duet | M | |||||

| C 410 | Humoreske – G minor | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 849 | I am glad, are You? [Galop de Salon] | Piano | M | ||||||

| I Skumringen [In Twilight] | Op 134 | Piano/Voice | M | ||||||

| C 824 | 1908 | I Think of You [Valse Serenade] | Piano | M | |||||

| Idag skal alting sjunge [Today everything will sing] | Piano/Voice | M | |||||||

| Idylle Norvegienne | Piano | M | |||||||

| C 682 | Impromptu (in G major) | Op 135 | Piano | M | |||||

| C 673 | Impromptu a la Valse | Piano | M | ||||||

| Impromptu for Pianoforte | Piano | M | |||||||

| C 744 | 1904 | In a Rush | – backside Foraars-Længsel incomplete | Piano | M | ||||

| C 882 | In Maytime [Intermezzo] | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 910 | In the Daylight [Moment musicale] | Piano | M | ||||||

| In the Springtime [Piece characteristic] | Piano | M | |||||||

| In the Twilight [Nocturne] | – To Mrs. P. M. Skartvedt; Remembrance of the Wedding-day – version of C 910 In the Daylight | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 804 | Iris [Waltz in G minor] | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 912 | Joyful Day in the Summer, A | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 833 | Joys of Summertime | – incomplete score | Piano | M | |||||

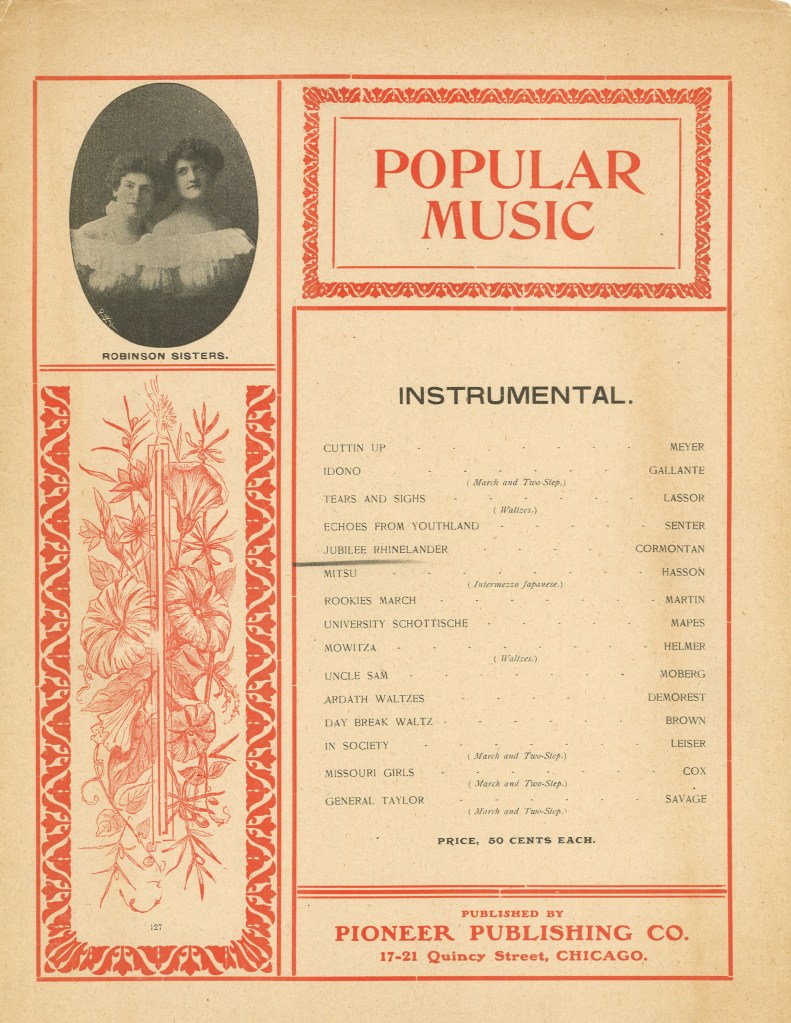

| 1905 | Jubilee Rhineländer, A | Op 58 | Piano | P | Pioneer Publishing Co. Chicago | ||||

| C 820 | King Eric and the Guardsmen [Paraphrase over Swedish Romance] | Piano | M | ||||||

| 1885 | Koerlighed et Livets Kilde [Love is the Source of Life] | – Published by Cormontan – Michelsen | Op 42 | Piano | P | Printed in Liepzig? | |||

| 1900 | L’Elegance | – also published by Cormontan in 1885 as La Eleganza, Menuet – Michelsen | Op 10 | Piano | P | Hatch Music Co. Philadelphia | |||

| C 908 | L’Etoile du Soir [Valse mélodique] | – incomplete score | Op 101 | Piano | M | ||||

| Little Song, A | – backside Wedding March | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 901 | Lonely Day, A | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 784 | Longing for the Spring [Valse de Salon] | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 401 | Longing from the Sea [ Paraphrase over Swedish Romance] | – same piece as below (C 821) | Piano | M | |||||

| C 821 | Longing from the Sea [Paraphrase over] | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 884 | Lovely Tharith [at end of piece: Elskelige tanker–Loving thoughts] | – Originally titled Lovely Eyes | Piano | M | |||||

| C 818 | 1907 | Lullaby | Piano | M | |||||

| C 803 | Lydia [Polkette] | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 417 | March | – Originally titled Turkish March | Piano | M | |||||

| C 472 | 3/27/1893 | Marshe religiosa | – Originally titled Offertoire Marche – Composed in Franklin, MN | Piano or Organ | M | ||||

| C 655 | Mazurka d’ème [Second Mazurka] | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 688 | Menuet melodique | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 907 | Moment Musicale | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 835 | Moment Musicale in A flat major [Caprice] | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 807 | Moonlight Polka | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 777 | Morceau à la Polska [From the North] | Op 121 | Piano | M | |||||

| C 913 | Morceau de Salon in G major | Op 79 | Piano | M | |||||

| C 691 | Morceau Rustique | – incomplete score | Piano | M | |||||

| C 846 | Mountain Dance [Halling] | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 623 | Music Piece in Norwegian Folktune [Fantasia] | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 625 | My Home [Moment Musical] | Op 74 | Piano | M | |||||

| 6/6 1885 | Naar mit Øie, trat af Moie [Fantasie Transcription] | – Tune by Ludvig Mathias Lindeman | Op 31 No 1 | Piano/Voice | M | ||||

| 1896 | Naar Solen gaar ned [When the Sun Goes Down] | – text by R Hammer -backside Aftenstemning July 1897. Text by Jorgen Moe | Piano/Voice | M | |||||

| C 753 | Ninetta Polkette | – incomplete score | Piano | M | |||||

| Ninetta Polkette | Op 61 | Piano | M | ||||||

| 1/16 1886 | Norske Turneres National-Festmarsch | – published by Cormontan in 1885 | Op 46 | Piano | M | ||||

| C 692 | Norwegian Dance Tune | – originally titled Norwegian Mountain Dance | Piano | M | |||||

| C 692 | Norwegian Dancetune (Halling). This score was donated to the KUBEN museum in Arendal, Norway | – similar to the other C 692 | Piano | M | |||||

| C 721 | 1901 | Norwegian Hymn | – backside: Aftensalme | Piano | M | ||||

| O, havde jeg Fuglen sin Vinge [Oh, to have the bird’s wings] | – text by Johan Selnes | Piano/Voice | M | ||||||

| O, Hjertens Ve! [Oh, the way of the heart] (Fantasi Transcription in F minor) | – Hymn tune: O Traurigkeit. Text: Johan von Rist (1637) | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 915 | One Day in the Spring [Galop de Salon] | – incomplete score – Originally titled Spring is Always Joyful! | Piano | M | |||||

| 3/3 1883 | Paa Sæteren [Fjeldljom] [Summer mountain pasture/cabin] | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 870 | Peony Rose, The [Intermezzo] | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 541 | Piece Fantasia [Morceau fantastique?Fantasistück] | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 605 | Poéme Lyrique [Lyrical Poem?Tonstück] | Piano | M | ||||||

| Polish Caprice | – incomplete score | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 736 | 1904 | Polish Lady, The [Piece a la Mazurka | – originally titled The Polish Countess | Op 126 | Piano | M | |||

| 1895 | Polka Fantasia over Swedish Song | Op 54 | Piano | P | Thompson Music Co. Chicago | ||||

| C 657 | Polka mélodique | Piano | M | ||||||

| Praeludium til Salmen O tank naar engang [O Happy Day When We Shall Stand] (Text by Wilhelm A. Wexels) | – Tune: Lobt Gott Ihr Christen Nikolaus Herman – backside Fest-Praeludium | Piano/Voice | M | ||||||

| C 879 | Remembrance | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 811 | Sad Memory | Op 132 No2 | Piano | M | |||||

| C 622 | Second Bagatelle [F minor] | Op 130 | Piano | M | |||||

| C 885 | Second Impromptu in G major | Op 136 | Piano | M | |||||

| C 414 | Second Waltz Caprice over Norwegian Folksong | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 611 | Shepherd’s Playing, The [Idyl] | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 823 | Shepherds Playing, The [Norwegian Musicpiece] | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 827 | 1908 | Solitude | Piano | M | |||||

| C 828 | 1908 | Song without Words | Piano | M | |||||

| C 613 | 1897 | Spanish Dance [Spanische Tänze and Danse Espagnole] | – incomplete score | Piano | M | ||||

| C 654 | Spanish Dance | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 607 | 1897 | Spanish Dance | – incomplete score – same piece as C 613 | Piano | M | ||||

| C 442 | March 1891 | Spanish Danse (Caprice) | – composed in St. Paul, MN | Op 97 | Piano | M | |||

| C 647 | Spanish Gipsy Dancer [Piece characteristic] | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 418 | Spring, The [Valse Brillante] | Piano | M | ||||||

| Summer Day | – one of two slightly revised works | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 868 | Summer Day | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 675 | Summer’s Greeting [Caprice] | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 748 | Sweet Memory [Waltz] | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 699 | Sweet Remembrance | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 845 | Tonepiece in norwegian Folktune [sic] | Piano | M | ||||||

| Twilight Thoughts [a Redorva – Salonpiece] | Piano | M | |||||||

| Under the Lindens [Intermezzo] | – also titled Under the Limetrees | Op 16 | Piano | M | |||||

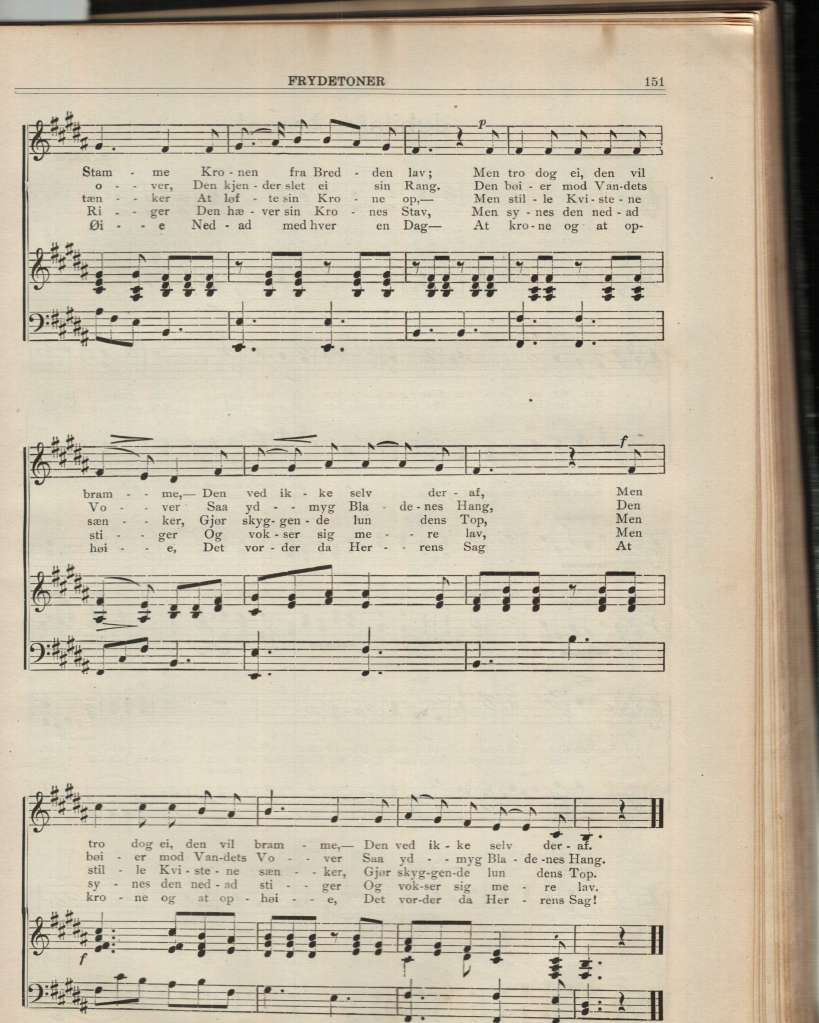

| Ungbirken [Young Birch] | – backside Eg Veit ei lite gente – text by Jørgen Moe – published (in the U.S.) in the Frydetoner hymnbook | Piano/Voice | M | ||||||

| Untitled # 2 [title worn away] (incomplete) (allegro) | Op 41(?) | Piano | M | ||||||

| Untitled #1 [title worn away] (incomplete) (Tempo di Polacca) | Piano | M | |||||||

| Untitled #3 [title worn away] (menuet) (Andante e tranquillo) | Piano | M | |||||||

| 1880 | Untitled #4 [title worn away] | Op 40 | Piano | M | |||||

| Untitled #5 (incomplete) | Piano | M | |||||||

| Untitled #6 (incomplete) (German text) | Piano/Voice | M | |||||||

| C 450 | Valse a l’etude | – backside Vi tro og troste paa en Gud | Op 25 | Piano | M | ||||

| C 271 | 1884 | Valse brillante | Op 33 | Piano | M | ||||

| C 316 | Valse brillante (A major) | Op 57 | Piano | M | |||||

| C 685 | Valse brillante (E major) | Op 140 | Piano | M | |||||

| C 801 | Valse brillante in F major | – also titled Lucy | Piano | M | |||||

| C 616 | Valse de Ballet | Op 75 | Piano | M | |||||

| C 423 | Valse de Salon | – incomplete score | Piano | M | |||||

| C 815 | Valse G major | Piano | M | ||||||

| 1/25 1876 | Ved Rokken. Text by Joh. Holm Hansen | – backside Bølgen -text by Joh. Holm Hansen – was published as No. 3 in Op 4 of Tre Sange by Warmuth Publishing | Piano/Voice | M | |||||

| Vi tro og troste paa en Gud [We believe and are comforted by God] | – text author: Magnus Brostrup Landstad (1802-1880) – backside Valse a l’etude | Piano/Voice | M | ||||||

| C 370 | 1889 | Vinterbillede [Winter Scene] | – incomplete score – text author unknown – backside En Damrungslund | Piano/Voice | M | ||||

| Waltz Capricious | – incomplete score | Piano | M | ||||||

| C 409 | Waltz elegant | Op 36 | Piano | M | |||||

| C 402 | Waltz Fantasia over a Swedish Song | Piano | M | ||||||

| 1895 | Waltz Gracious | – There are two copies of this piece – Jorgensens kept one copy | Op 53 | Piano | P | Johnson and Lundquist, Minneapolis | |||

| C 346 | 1888 | Waltz Impromptu | -draft copy in pencil | Piano | M | ||||

| C 722 | Wedding March | – backside A Little Song | Piano | M | |||||

| C 869 | Winter Rose, The | Piano | M | ||||||

Composition Dates

Theodora Cormontan dated only a small percentage of her compositions, making the determination of when she wrote most of her music problematic. She did mark about 75% of her music with what I call a “Cormontan number.” This number seems to be a type of cataloging number, perhaps a system she used when she owned and operated her own music rental company in Arendal, Norway in the 1870’s-1880’s.

The first list below consists of pieces Cormontan assigned both a year of composition and a Cormontan number. The list is in chronological order:

1884/C 271 Valse brillante

1888/C 346: Waltz Impromptu

1889/C 369: En Dæmrings stund

1889/C 370: Vinterbillede

1891/C 442: Spanish Dance (Caprice)

1891/C 445: The Dancing Girl (Musical Moments)

1893/C 472: Marshe religiosa

1897/C 613: Spanish Dance

1901/C 721: Norwegian Hymn

1904/C 736: The Polish Lady

1904/C 744: In a Rush

1907/C 818: Lullaby

1908/C 824: I Think of You

1908/C 827: Solitude

1908/C 828: Song without Words

It seems safe to say that there is a direct correlation between the Cormontan number and the year the piece was composed: the higher the Cormontan number, the later the composition.

The next list includes Cormontan compositions that carry both a Cormontan number and an Opus number, arranged sequentially from the lowest to the highest Opus number. All of them are in manuscript (M) form; I am unaware that any were ever published:

Op 25/C 450: Valse a l’Etude (M)

Op 33/C 271: Valse brillante (M)

Op 36/C 409: Waltz elegant (M)

Op 57/C 316: Valse brillante (A major) (M)

Op 70/C 899: Chanson sans paroles (M)

Op 74/C 625: My Home (M)

Op 75/C 616: Valse de Ballet (M)

Op 76/C 648: Danse Rustique Norvegienne (M)

Op 79/C 913: Morceau de Salon (M)

Op 83/C 748: Fleur Printamiere (M)

Op 97/C 442: Spanish Dance (Caprice) (M)

Op 101/C 908: L’Etoile du Soir (M)

Op 115 & 135/C 682: Impromptu (in G major) (M)

Op 124/C 800: Dream of Life (M)

Op 125/C 630: Chanson de Bergerette (M)

Op 126/C 736: The Polish Lady (M)

Op 128/C 873: Dagny—Polka Caprice (M)

Op 129/C 620: Bagatelle in D major (M)

Op 130/C 622: Second Bagatelle (M)

Op 132 # 2/C 811: Sad Memory (M)

Op 133/C 809: Floweret (M)

Op 136/C 885: Second Impromptu (M)

Op 140/C 685: Valse brillante (E major) (M)

The correlation between the Opus number and the Cormontan number is difficult to ascertain. It would appear that the Opus number would have little to do with the Cormontan number.

The third list consists of compositions that include an Opus number and a date, listed chronologically by date. This list includes some manuscript (M), some published (P), and one piece that we have in manuscript but we know was published in Norway (M/P):

1880/Op 40: Untitled #4 (M)

1884/Op 33: Valse brillante (M)

1885/Op 31: Naar mit Øie, trat af Moie (M)

1885/Op 42: Koerlighed et Livets Kilde (P)

1885/Op 44: Honor March (M/P)

1886/Op 46: Norske Tuneres National-Festmarsch (M/P)

1891/Op 97: Spanish Dance (Caprice) (M)

1895/Op 54: Polka Fantasia over Swedish Song (P)

1900/Op 10: L’Elegance (P)

1904/Op 126: The Polish Lady (M)

1905/Op 58: A Jubilee Rhineländer (P)

1906/Op 59: Danse de la Duchesse (P)

A stronger correlation between Opus number and date can be seen. Generally, compositions with an Opus number in the 40s and lower were composed in Norway and in the 50s and higher in the US. This correlation is further strengthened when one realizes that Op 10 was actually published in Norway in 1885 and subsequently published in the US in 1900, (the edition we have). It may also be noted that Among Norwegian Mountains, Op 3, was published by Warmuth in 1875. We have a manuscript version that appears to be a revision of the published version.

Conclusion: It remains challenging to date any of Theodora’s compositions that she did not date herself. Even works with a higher Cormontan number may have been substantially composed in Norway or even Denmark and only completed in the USA. Still, the strong correlation between the Cormontan # and the date of composition (when both are indicated on the score) makes it probable that the approximately 75% of scores with a Cormontan # can be dated within a few years of composition. At this time it appears that approximately 75% of the works in our possession were either completely composed or at least finalized in the United States between 1887 and around 1915. The other 25% were written in Europe, likely in Norway, and probably between approximately 1870-1886.

Cecilie Dahm Chapter

The following is an electronic translation of the first chapter of

Dahm, Cecilie. Kvinner Komponerer: Ni portretter av norske kvinnelige komponister i tiden 1840-1930. Oslo: Solum Forlag A.S., 1987.

Translation: (Dahm, Cecilie. “Women compose: nine portraits of Norwegian women composers between 1840-1930.” Oslo: Solum Publishing, 1987).

The first chapter of Cecilie Dahm’s book is a general discussion of the challenges women composers faced in Norway during Theodora Cormontan’s lifetime. Dahm included a paragraph about Theodora which may be found at the end of the following entry.

A glance at the times [1840-1930] and the role of women in music.

Many ingenious theories have been made over time regarding women’s “natural “ inability to create music, theories which often conclude that, while women have distinguished themselves as performers, composition is a discipline that has not produced a single female composer of greatness, even–as it so often is described–when they have been assessed less critically than men. The few female composers have at best created small, unpretentious compositions, typically songs and piano pieces.

In Europe and America there has been, in recent times, comprehensive research in this area. Historical sources have been studied and scores have been pulled out from libraries and archives, and a whole new picture emerges, a picture that shows that over the centuries there have been a number of significant female composers. Many were highly regarded in their day but, to a far greater extent than men, they have been subject to the changing conditions of their times and limited by historical and social conditions.

In Norway, where art music does not have as long a tradition as elsewhere in Europe, we remember only a few Norwegian female composers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Among these, there is only one name that is widely known today–Agathe Backer Grøndahl. That she was the great female figure in Norwegian music between 1840-1930 is beyond doubt. She is duly mentioned in encyclopedias and historical works, and a fairly significant amount of her music is still heard.

But while Agathe Backer Grøndahl was the greatest, she was far from the only female Norwegian composer of her time. Music historiography in Norway has not been better than other countries. It confirms all our notions of music as men’s work. But the reality is that in Norway women have engaged in the art of music not only as interpreters, but also as creators.

A 1986 list compiled by Kari Michelsen at the University of Trondheim contains no less than 120 names of Norwegian women who had their music published by Norwegian publishers before 1920. The actual figure is probably higher. It must be noted that many of these women were not significant composers, but the figure shows that women have composed in Norway and that publishers have found it profitable to publish their music. This suggests that there has been a market for music composed by women. It has been used in homes, in teaching and—from what we can see in old concert programs–often in public performance.

Women who had the opportunity to cultivate skills in musical composition usually belonged to the upper class; a typically more liberal group that supported the opportunity for women to receive training. But the educational opportunities for women were inadequate. In the 1700’s and 1800’s there were clear roles for music and for women. Training in piano, singing and harmony belonged to the young girl’s upbringing. But professional requirements were rarely asked, even of those with special abilities. For women, music composition was seen as a hobby, like drawing, embroidery and other domestic tasks.

Consequently, women were precluded from training in the compositional skills that are required to compose in larger forms and for larger instrumental ensembles. Women were provided little opportunity. Though some Norwegian women studied at music conservatories in Leipzig, Berlin and Paris in the second half of 19th century, it was mainly for training in piano and singing. Playing the organ, orchestra conducting, choral conducting, and playing wind instruments were areas typically reserved for men. When Sweden’s first female organist, Elfrida Andree (1841-1929), graduated from the conservatory in Stockholm in 1857, it was through a special dispensation; also when she entered a position as organist four years later. When the Organist School–later the Oslo Music Conservatory–was founded in 1883, there was no question that women would be included. Nevertheless, women did not apply for orchestra positions, nor was there available to them public positions as organists or chapel masters. Such jobs entailed practical knowledge of instruments and, in many cases, compositional duties.

Women’s musical education was thus characterized by superficiality, their instrument of choice being limited to the piano and singing. This was also rooted in the prevailing conditions in the upper class in the 1800’s. It included an expectation of family life which brought with it making music in the family circle. During the 1700’s the piano—the defining musical instrument of the upper class–made its appearance in Norway. Every self-respecting bourgeois family had a piano in the living room. Here the woman’s role was that of the singing and piano-playing wife and daughter, not only a cherished staple of family and social life, but a plus for the family’s social status. The image of the woman at the piano in plush, furnished interiors is a well-known motif from this period. And the perception of music as the most emotional of the art forms also entered the picture. For conveying intimate emotions, the woman was considered particularly suitable to perform music that characterized music for the home; parlor music, “song with its heart on its sleeve,” the intimate little piano piece, and dance pieces like the gavotte, mazurka, waltz and polonaise. Newspaper ads from the period reinforced this attitude.

Women’s music-making in the home has had an impact on the general music education. But women experienced highly limited opportunities for development and training at a higher level. There was no tradition to support the professional woman composer. We can assume that many an artist has been destroyed under these conditions.

There was nothing to break this social pattern. When a woman still managed to do it, it was because, in addition to being gifted, she was fortunate regarding her economic situation and lived in a liberal, arts-friendly environment. These women, after studying abroad, could become professional practitioners or educators. But whether they were professional or just clever amateurs, they worked within a tradition where the two functions, performer and composer, were closely linked. That women composed was not uncommon. But the culture severely limited what they could compose. They were expected to compose only songs and piano pieces; only the miniature forms. Here were the invisible boundaries of what was expected of women as creative musicians. As long as they stayed within those limits, they were not only accepted by their environment, they were encouraged and viewed favorably by music critics when their music was published or was performed at concerts. Reviewers frequently made a point of noting when the composers were women. A piece would be described as a gracious female work, or a composer as a talent which does not tend to be present in women. Regarding a couple of songs by Sophie Irgens, the Nordic Music Journal wrote in 1892 that they are what one does not often find with female composers; they were written with humor. Regarding some romances presented by Marta Vestbe, a music magazine in 1911 wrote that the songs were different from what the ladies ordinarily performed in this area.

The most prominent of the Norwegian music critics in the period was Otto Winter Hjelm (1837-1931). He himself was a composer, a conductor, and also a sought-after teacher. As a music writer with the longstanding newspaper Aftenposten, he had great influence on our music scene in the 19thcentury and into the 20th. He was a noteworthy person. But he appears to be skeptical when it comes to female composers. Another music critic and composer, Per Reid Arson (1879-1954), appeared somewhat later. Though not as influential as Winter Hjelm, his voice still carried crucial importance for at least one of our female composers, Anna Lindeman (1859-1938). She belonged to the famous musical Lindeman family and was trained as a pianist. As one of our greatest piano teachers of the time, she was for many years associated with the Conservatory of Music in Oslo. When she was about 70 years old she completed a four movement string quartet on which she had worked for a long time. According to her son Trygve Lindeman, later director of the Conservatory of Music in Oslo, she considered her composing more as a hobby, but she still wished to have the quartet published. However, she showed it to Per Reid Arson, and he stated that he did not think it was compelling enough; that it was too lightweight.

This assessment reflects his thoughts about women composers in general. He expresses these thoughts in the music magazine Tone Art in December 1932, where he writes an article mulling over women’s lack of abilities as composers, noting that they rarely appear even among the names of less significant composers. He admits, however, that

“some handsome song or the most successful smaller piece could probably be produced by the common female composer. We have experienced that. But, it is typical that when women compose in the larger musical form, logic is betrayed and the music lacks proportion.”

He then rushes to add that he does not mean this as a criticism of women. He values them highly, even though statistics prove they cannot compose.

The authority had thus spoken, and Anna Lindeman’s string quartet fell into oblivion, where it remained for half a century. It collected dust in the library’s music collection until 1983, when the London String Quartet recorded it on the Norwegian label SIMAX, enriching the Norwegian Chamber Music repertoire with an exceptionally beautiful and well-written piece of music.

Some of our women composers excelled in organization. In the early 1890’s Fredrikke Rynning Waaler (1865-1952) founded Hamar’s first orchestra, where she served as concertmaster. Waaler is the exception when it comes to women’s instrument of choice. She played the violin, and in 1885 was a first violinist in the Music Association orchestra in Oslo. Olga Bjelke Andersen (1857-1940) formed the Drammen amateur orchestra, a forerunner of the later Drammen professional orchestra. She even served as director and conductor of the orchestra. Both of these women wrote songs, piano pieces, and choral works. Olga Bjelke Andersen also composed orchestral music, including the stage works East of the Sun and West of the Moon and Princess Rosy, listed on the National Theatre programs in 1906 and 1908 respectively.

Towards the end of the 1800’s, concurrent with the emergence of the feminist movement, some of our women composers began to gain a clearer understanding of their abilities and their work as creative musicians. They wanted education on an equal footing with their male counterparts, and they sought government assistance in the form of scholarships and grants. Government scholarships and endowments followed, with the Church & Ministry of Education responsible for distribution. Applications from Norwegian musicians, performers as well as composers, is preserved among Church and Ministry of Education documents in the National Archives in Oslo.

The first applications from female composers that noted clearly that they wanted to study composition were received in 1890. These came from Borghild Holmsen and Mon Schjelderup, who in subsequent years would reapply eight and six times respectively. Other applications came from Inga Lærum Liebich in 1893 and 1894, Inger Bang Lund in 1897 and 1907, and Signe Lund in 1898 and 1900. None of these applications were granted. In the same period (1890-1907) twelve male composers received funding from these sources, some of them several times, for a total of 24 grants.

A record of the rationale for this distribution does not exist, but a review of the Church and Ministry of Education document collection seems to show that women athletes were accepted and allocated funding on a par with their male counterparts. Women composers were also accepted, but only as long as their compositional training was an additional, non-funded part of their creative activity.

The first woman Norwegian composer who was granted public funding was Pauline Hall (1890-1969). In 1917 she received an endowment of $400.00 and, in 1919, a Government grant of $1500.00. She is the first woman to append the word “Composer” to her signature. This heralded a new generation of women composers in Norway, women who would eventually be seen as equal to their male counterparts. The 19th century bourgeois parlors were gone. To prove that Norwegian women composers have broken down some of the barriers of gender discrimination, the Composers Association membership list of 1987 includes 72 women. Disparity in numbers between male and female composers still exists; however, this is a question that falls outside the scope of this presentation.

. . . . . . .

Cecilie Dahm’s book goes on to devote a chapter each to nine Norwegian composers from 1840-1930. Theodora Cormontan is not one of the nine composers. At the end of her book Dahm devotes a paragraph each to a number of other Norwegian women composers, and Theodora is included here. The following is an electronic translation of the paragraph devoted to Cormontan:

Theodora Cormontan was born in Beit stad in Nord-Trøndelag. While still young she moved to Arendal and grew up as a priest’s daughter. She received her first lessons from the organist and town musician, Friedrich Toschlag. Later she received instruction in Copenhagen. In her hometown of Arendal she appeared frequently as a singer at the local concert hall and was a central figure in the local culture. She started her own music lending library and music publishing house. In 1887 she left Norway with her father and sister to settle in Iowa [Minnesota] in the United States. Here, she lived the rest of her life as a music teacher. She published some piano pieces and songs, among them “Loud from the heavenly heights” and “Among the Mountains.”

Cormontan Music Library

Cormontan Music Library

Along with the manuscripts and published works by Theodora Cormontan, the music collection given to the Jorgensens by Barb and Roger Nelson included several volumes of music by other composers. These scores either bear Theodora’s signature or another identifying feature that makes them almost certain to have belonged to her. It would seem likely that Theodora regarded this music favorably, since she owned it, and it is also quite possible that some of these works influenced her own writing.

The scores include:

Classic Songs by the Best Composers, B.F. Banes and Co., Copyright 1893. I have never heard of this company. It looks like it was publishing in the 1880’s-1890’s. The album has a drawing of Edvard Grieg on the cover, which may have attracted Theodora to it. The volume contains some composers who have drifted into obscurity, like Denza and Barnby, but also includes Faure, Handel, Mozart, and Brahms. There are two pieces by Grieg (Solveig’s Song and I Love Thee) and one by Kjerulf. I wonder if it frustrated Theodora that these Nordic composers songs were presented in only English and German?

Romancer og Sange (Romances and Songs) by Edvard Grieg, published in 3 volumes by Wilhelm Hansen, Copenhagen. No copyright date, though on the title page it says (in Danish) “New, revised edition by the composer.” Volume 1 includes Grieg’s Op. 4, 5, 9, 10, and 15. Volume 2 includes Op. 18, 21, and 22. Volume 3 includes Op. 23, 24, 26, and two songs noted as “without an opus.” These works were originally published in the 1860’s-1870’s, so Theodora almost certainly purchased them in Norway or on a visit to Denmark. It appears to me that Grieg was a major, if not the major, influence on Cormontan the composer.

The Art of Finger Development by Carl Czerny, Op. 740, published by Theodore Presser, Philadelphia. No copyright date. Theodora taught piano, or perhaps used this exercise book for herself as well.

The American Artist’s Edition, Album, Vol. 1: A Choice Collection of Pianoforte Pieces by the Old Masters and Best Modern Composers, published by The John Church Co., Cincinnati. Copyright 1890. This company published from the 19th century into the 20th. They were bought out by Theodore Presser in 1930. John Philip Sousa is one of their published composers. Most of the composers in Cormontan’s volume are rarely performed today, but it does contain Grieg’s Four Lyric Pieces as well as works by Widor, Tchaikovsky, and Paderewski. The music is protected in the “Gem” music binder, manufactured by C.S. Fowler in Minneapolis.

Musique Moderne, Compositions pour Piano, No. 1: Bleu d’Azur by J.H. Hecker, published in Bruxelles (Brussels). Copyright 1887. This does not contain Theodora’s autograph, but has a stamp on it from the music publishers Brodrene Hals in Christiania (Oslo), so I am guessing it was hers.

12 Melodier til Digte af A. O Vinje Op. 33 by Edvard Grieg. Published by Wilhelm Hansen, Copenhagen. This is the first six pieces from this important opus, including Varen. It does not have Theodora’s signature, but is stamped by her music rental company in Arendal, so it was hers. This score was donated in 2015 to the KUBEN museum in Arendal, Norway where a collection of Cormontan’s other rental music resides.

Kunkel’s Musical Review, March, 1901. Published by Kunkel Brothers of St. Louis. It contains “32 pages of music and musical literature,” most notably, Paderewski’s Menuet, Op. 14, No. 1.

Lindeman’s Koralbog. This edition was published by Augsburg Publishing in Minneapolis. The original copyright for this edition is 1899, with this printing from 1916. The title page when translated reads:

Chorus Book, containing Music for Hymnal for Lutheran Christian [Church] in America,

for Landstadts, Synodens and other Hymnals, to be used for mixed Choir, Organ or Pianoforte.

———

Ludv. M. Lindeman’s Chorus Book with an Addition collected and composed by Oluf Glasøe.

[Published according to standards committee permission.]

Augsburg Publishing House, Minneapolis, Minn. 1899.

Lindeman’s original Salmebog was published between 1871-1875 for use in the Church of Norway. Theodora’s signature is found on the title page. On the next page she writes “Tilhore [Property of] Theodora Cormontan. 1922. A.H.H. Decorah, Iowa.” Theodora says a lot in these few words. They tell us that music in general, and specifically church music, plays a role in the last year of her life. They suggest that she remains alert and active. It would appear that Norwegian is the primary language spoken among the residents of the home.

Published Compositions

The following is a list of compositions Theodora Cormontan published in Norway, compiled by Norwegian musicologist Kari Michelsen. Cormontan’s music was published by Warmuth from 1875-1879. Beginning in 1880, she published her music herself. The first list is in the original Norwegian, followed by an English translation. The lists are ordered by year of publication.

Komposisjoner: Kari Michelsen: Musikkhandel i Norge Kapittel 10, 218-219

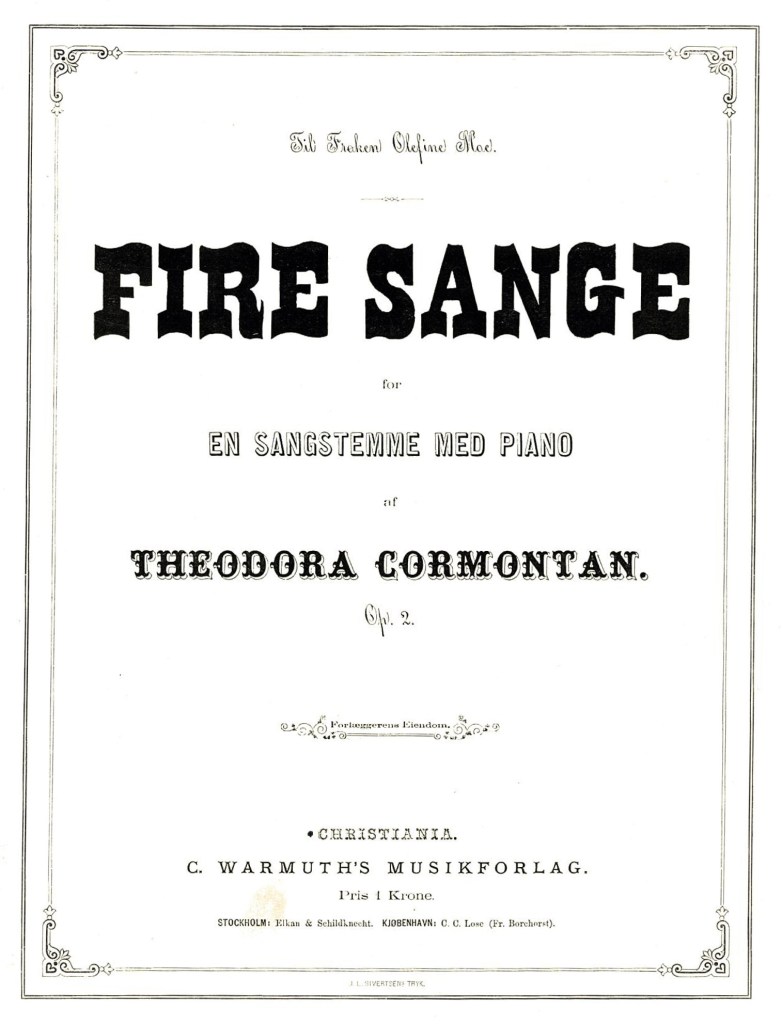

4 Sange op. 2 /Hvad jeg elsker (H C Andersen [poet]), Warmuth 1875

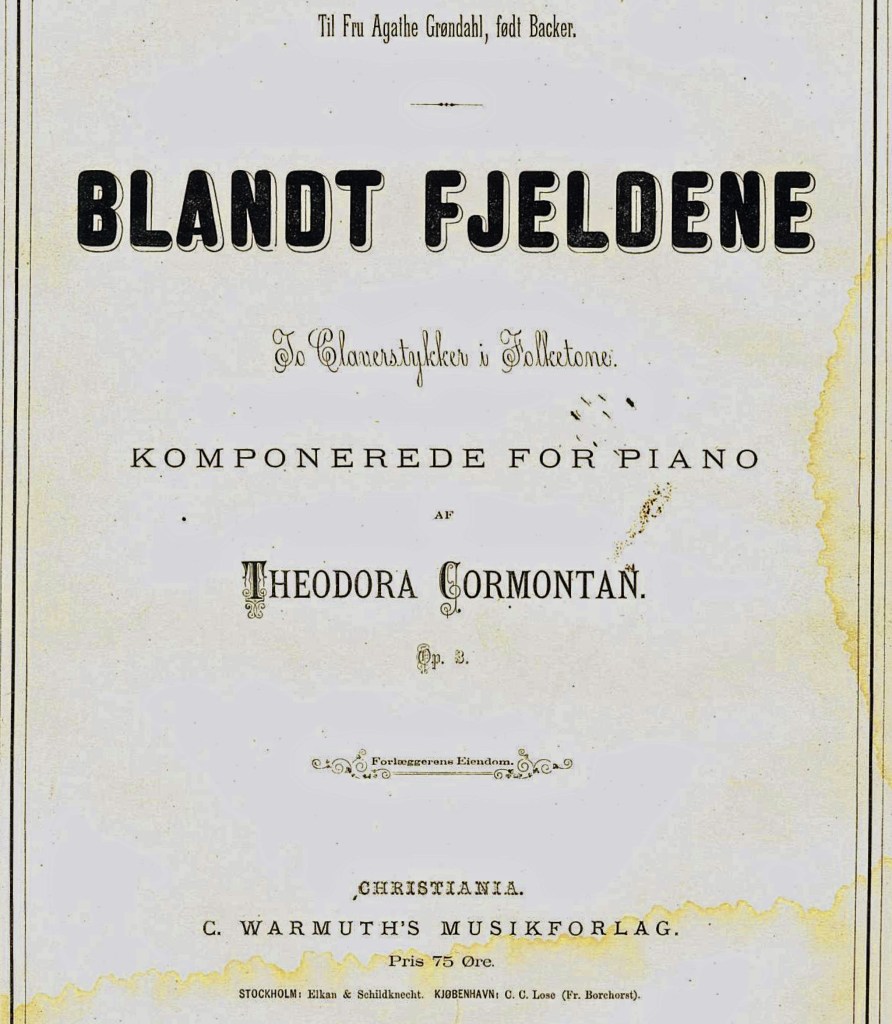

Blandt Fjeldene op. 3 (p2 [piano, 2 hands]), Warmuth 1875

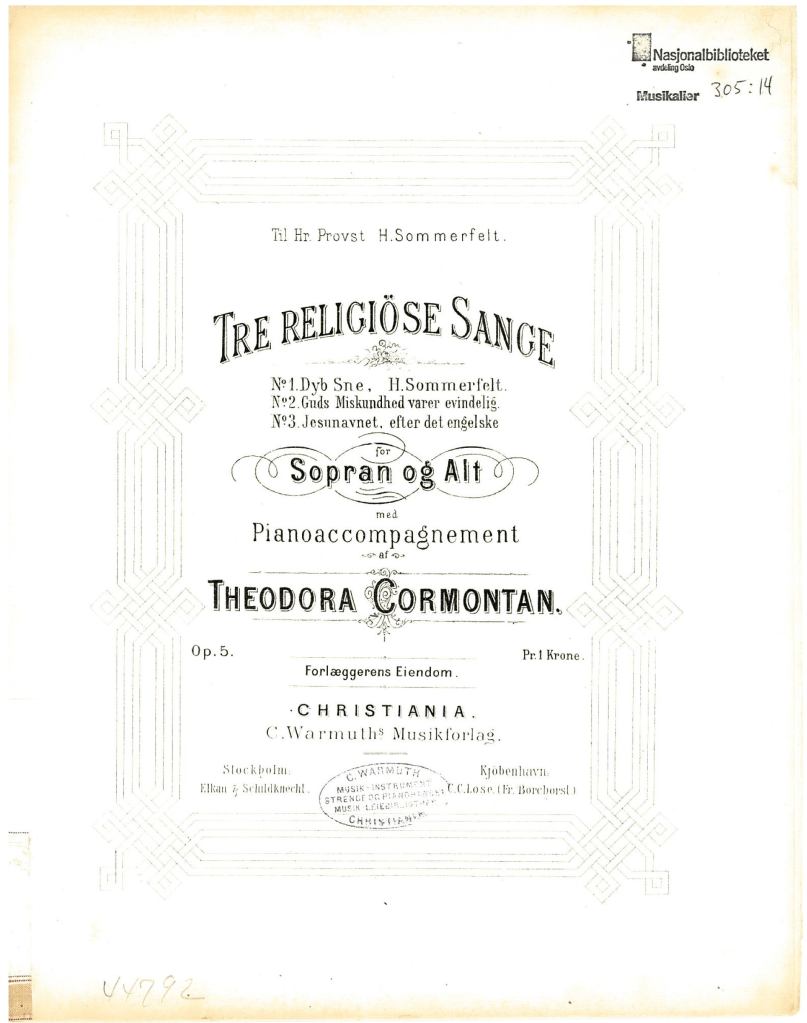

3 Religiøse Sange op. 5 /Dyb Sne (2s-p [2 singers-piano]), Warmuth 1877

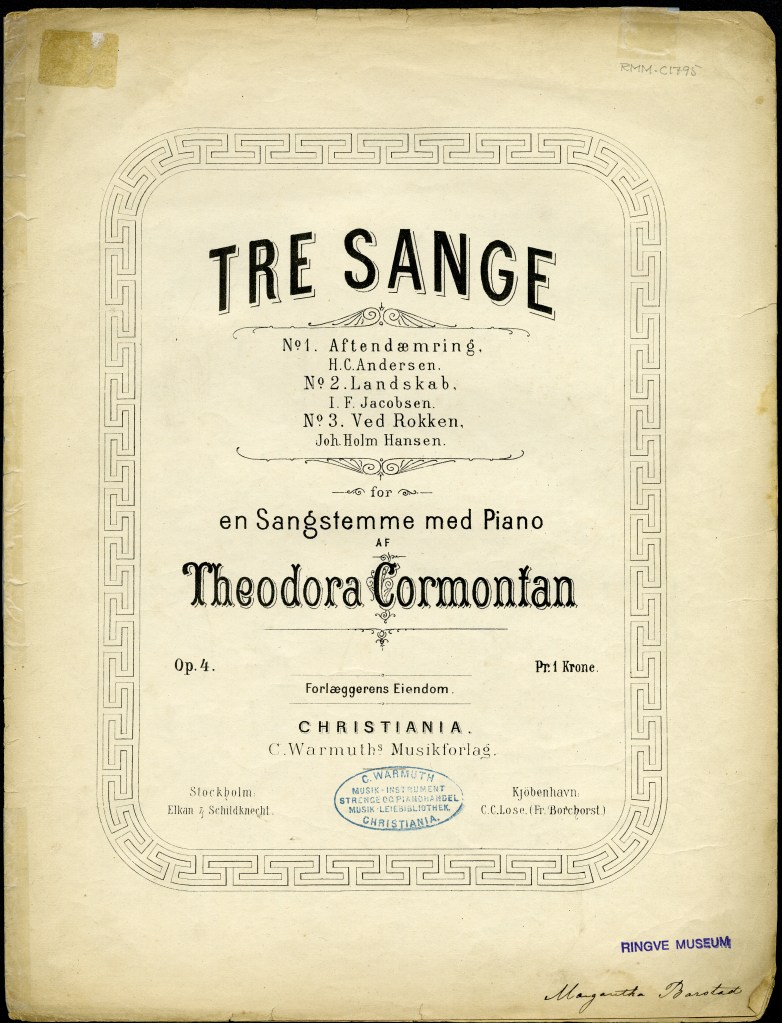

3 Sange op. 4 /Aftendæmring (H C Andersen), Warmuth 1877

4 Sange op. 6 /Holder du af mig (Bjørnson), Warmuth 1879

4 Sange op. 1 /Det døende Barn (H C Andersen), Cormontan c 1880

Hvad ønsker du mer op. 8.1(F W Krummacher) (2s-p), Cormontan c 1880

Fred til Bod for bittert Savn, Fantasie-Transcription (p2), Cormontan 1883

Herre Jesu Christ, Fantasie-Transcription op. 36 (p2), Cormontan 1885

Honnør-Marsch for norske Turnere op. 44 (p2), Cormontan 1885

Kjærlighed er Livets Kilde, Fantasie-Transcription op. 42 (p2), Cormontan 1885

La Eleganza, Menuet op. 10 (p2), Cormontan 1885

(above) This is the USA publication of the score.

Norsk Konge-Polonaise op. 43 (p2), Cormontan 1885

Norske Turneres National-Festmarsch op. 46 (p2), Cormontan 1885

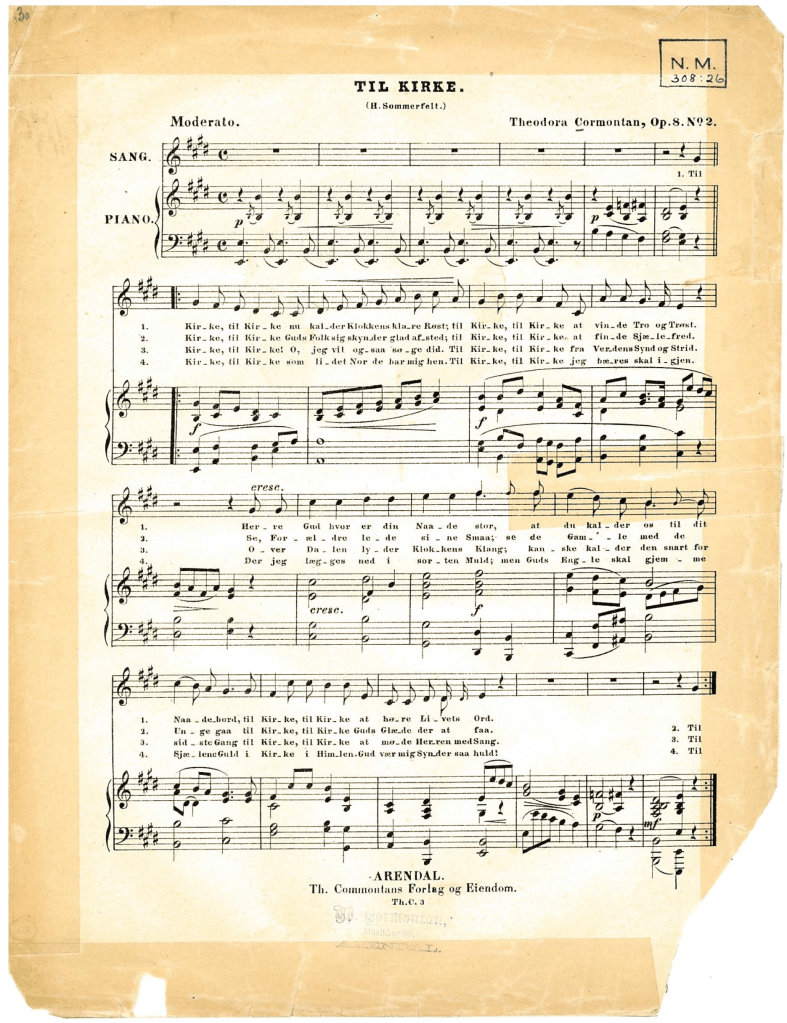

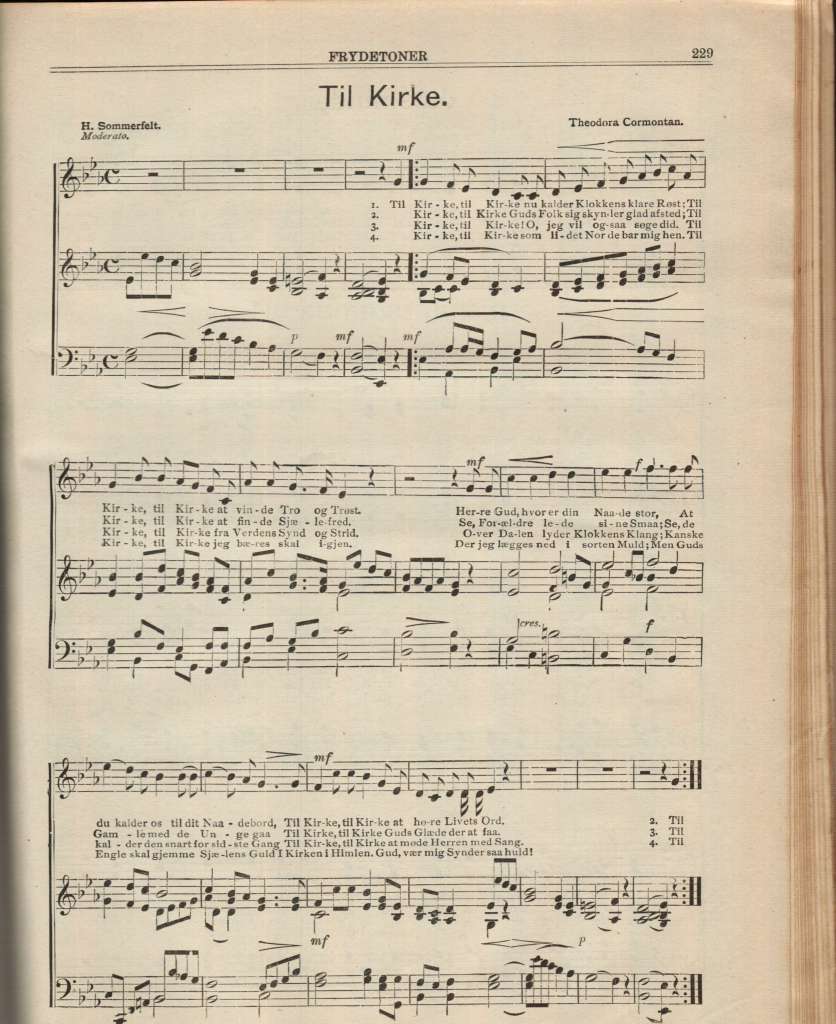

Til Kirke op. 8.2 (s-p), Cormontan 1885

The 12/23/1883 edition of the Vestlandske Tidende lists several works composed and published by Cormontan not noted in Michelsen’s list. These include “Havfruens Sang. Lyrisk Tonestykke” as well as 4 Fant.Transcriptioner. “No. 1 “Her vil ties, her vil bies,’ “No. 2 Den store, hvide Flok vise,” “3. ‘dybe, stille, stærke, milde.’ The fourth piece, “Fred til Bod for bitter Savn” is noted by Michelsen.

Compositions: Kari Michelsen, Music Publishers in Norway, Chapter 10, 218-219

4 Songs op. 2 / What I love (H C Andersen), Warmuth 1875

Among Mountains op. 3 (p2), Warmuth 1875

3 Religious Songs op. 5 / Deep Snow (2s-p), Warmuth 1877

3 Songs Op. 4 / Twilight (H C Andersen), Warmuth 1877

4 Songs op. 6 / If you like me (Bjornson), Warmuth 1879

4 Songs op. 1 / The Dying Children (HC Andersen), Cormontan c 1880

What would you like more?. 8.1 (F W Krummacher) (2s-p), Cormontan c 1880

Peace of penance for bitter Longing, Fantasie-Transcription (p2), Cormontan 1883

Lord Jesus Christ, Fantasie-Transcription op. 36 (p2), Cormontan 1885

Honor March for Norwegian Turners (Gymnasts) op. 44 (p2), Cormontan 1885

Love is the Source of Life, Fantasie-Transcription op. 42 (p2), Cormontan 1885

Elegance, Menuet op. 10 (p2), Cormontan 1885

Norwegian King-Polonaise op. 43 (p2), Cormontan 1885

Norwegian Turners (Gymnasts) National Festival March op. 46 (p2), Cormontan 1885

The Church Op. 8.2 (s-p), Cormontan 1885

The 12/23/1883 edition of the Vestlandske Tidende lists several works composed and published by Cormontan not noted in Michelsen’s list. These include “The Mermaid’s Song. Lyrical Piece” and 4 Fantasy Transcriptions: 1) “Here will be silenced,” 2) The big, white Flock we see,” and 3) “deep, quiet, strong, gentle.” The fourth transcription, “Peace of penance for bitter Longing,” was listed by Michelsen.

The following piano pieces by Theodora Cormontan were published in the United States:

Waltz Gracious, Op 53, Johnson and Lundquist, Minneapolis, (n.d.)

Polka Fantasia over Swedish Song, Op 54, Thompson Music Co. Chicago, 1895

The Dream, [Waltz Caprice], Op. 56, Thompson Music Co. Chicago, 1895

L’Elegance [also published in Norway in 1885 as La Eleganza, Menuet] Op 10, Hatch Music Co., Philadelphia, 1900

A Jubilee Rhineländer, Op 58, Pioneer Publishing Co., Chicago, 1905

Danse de la Duchesse, Op 59, publisher unknown, 1906

Published Hymns

Published Hymns

Despite leaving her music publishing business in Arendal, Norway in 1887, it is clear that Theodora Cormontan continued to aspire to being a published composer in the United States. While a serious injury delayed her publishing ambitions, she was well enough by the early 1890’s to see several of her hymns published.

Ungdommens Ven (The Youth’s Friend) is a religious magazine for young people published from 1890-1916 by the K.C. Holter Publishing Company, Bernt B. Haugan and Nils Nielsen Rønning, editors. Frydetoner (Joyful Songs) is a collection of choral music that first appeared in Ungdommens Ven in the early 1890’s. Six hymns composed by Theodora Cormontan appeared in Ungdommens Ven between 1891-1894 and are included in the first two books (published in one volume) of the Frydetoner, first published in the mid-1890’s.

These are the dates, pages, and titles of the hymns that first appeared in Ungdommens Ven:

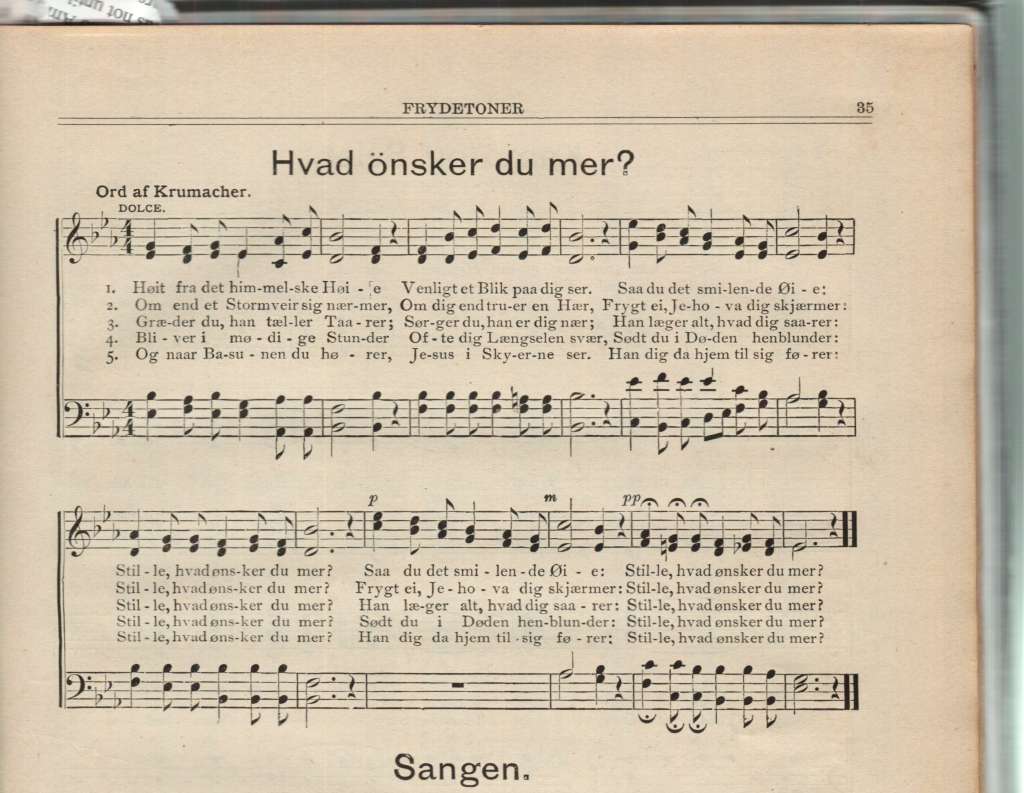

5/1891, p 79: Hvad ønsker du mer? (What would you like more?) This hymn is unattributed but was composed by Cormontan.

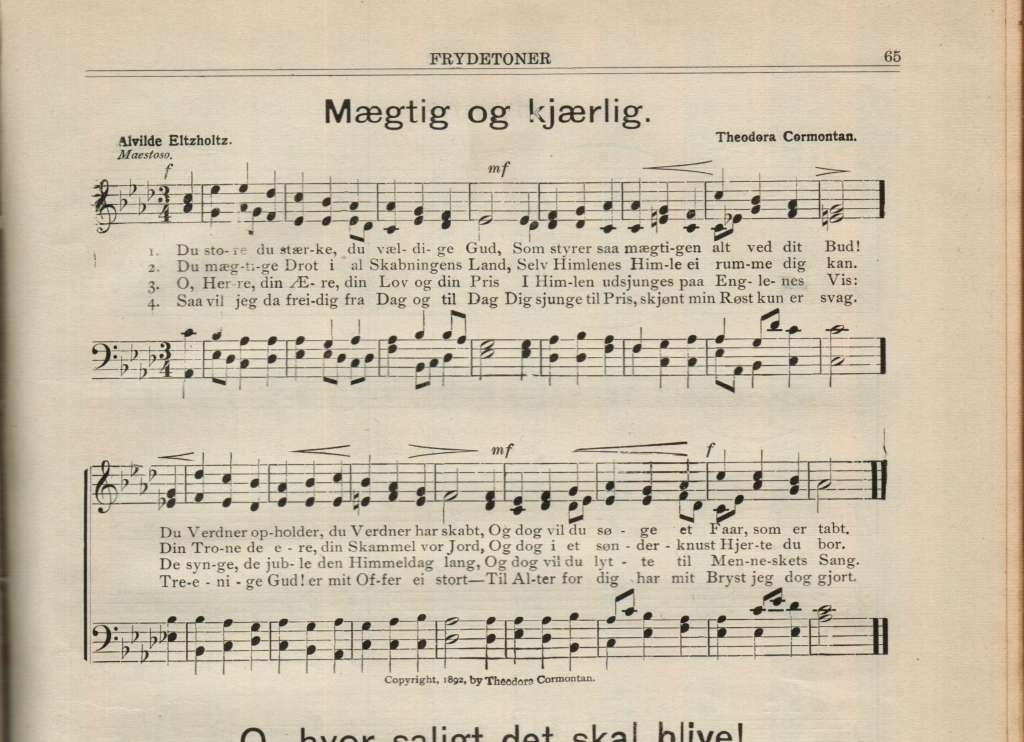

3/1/1892, p 78: Mægtig og kjærlig (Mighty and loving)

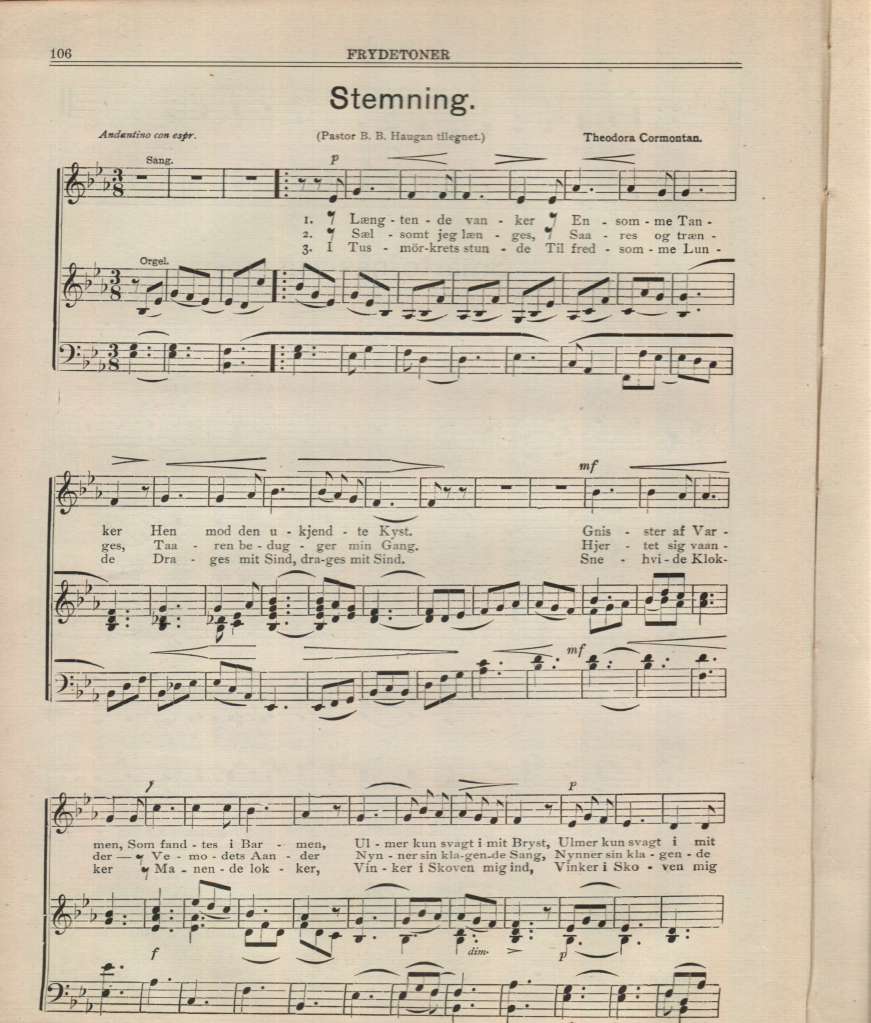

6/1/93, p 174-75: Stemning (Mood/Sentiment)

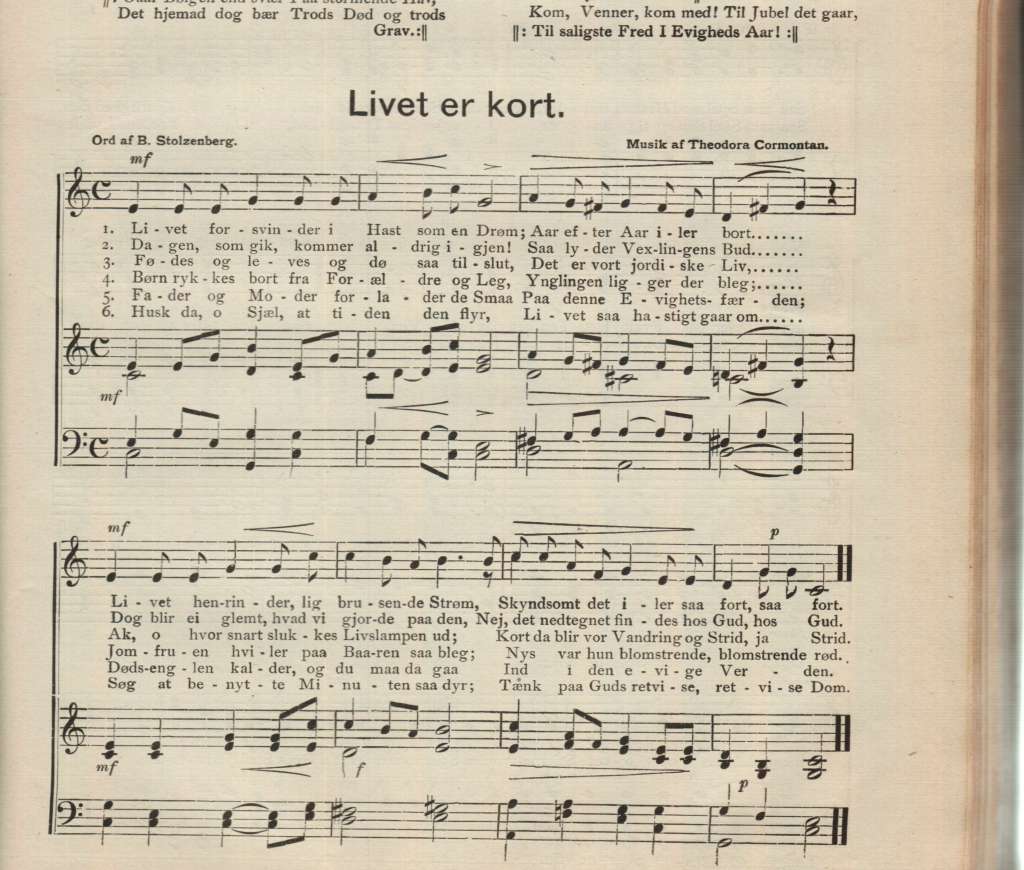

7/15/93, p 223: Livet er kort (Life is short)

8/1/93, p 239: Til kirke (To church)

9/15/94, p 350-51: Ungbirken (Young birch)

These are the titles, pages, and books where the Cormontan hymns were first published in the Frydetoner:

Hvad ønsker du mer?: p 35 first book

Mægtig og kjærlig: p 65 first book

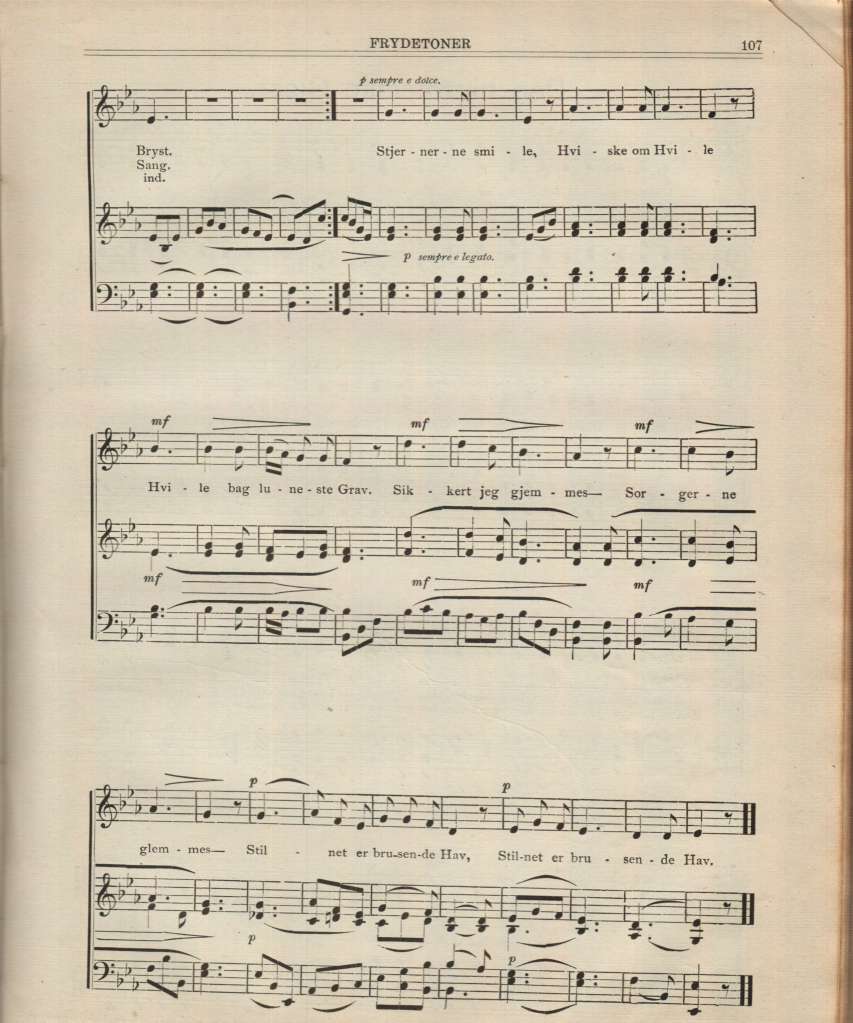

Stemning: p 106 first book

Livet er kort: p 121 first book

Ungbirken: p 150 second book

Til kirke: p 229 second book

“Hvad ønsker du mer?” (op.8.1) and “Til kirke” (op. 8.2) were published by Theodora’s own publishing house in Arendal, Norway in 1880 and 1885, respectively. “Ungbirken” also exists in a manuscript version that likely dates from 1882. It is unknown if the other hymns were also composed in Norway or if any were written in the United States.

In addition to these two sources, there is the following:

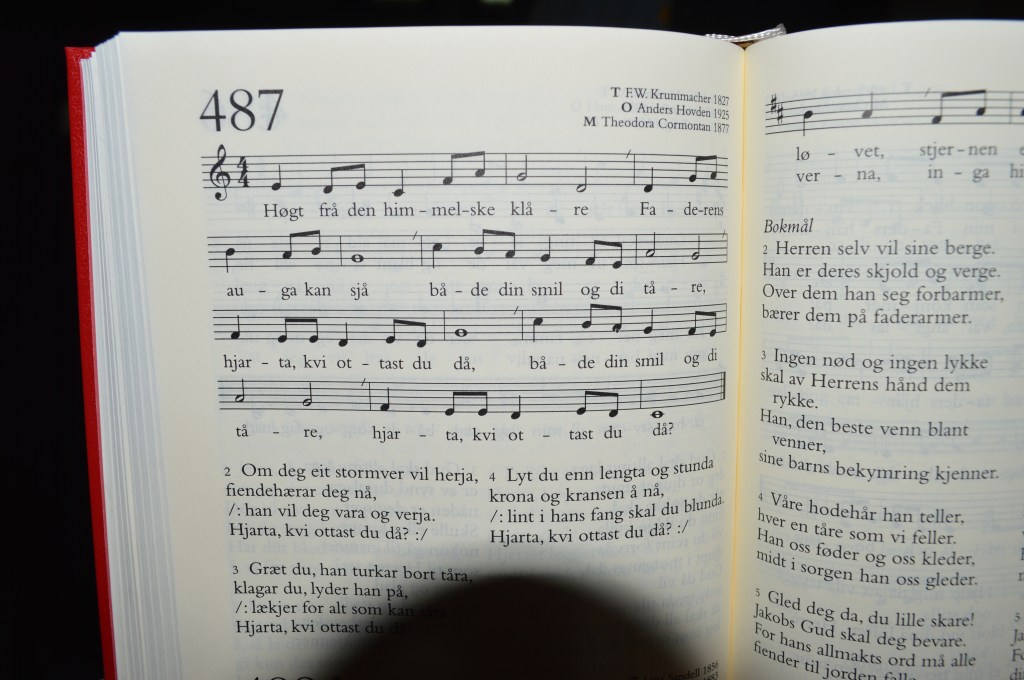

Sangbogen: en ny samling af aandelige sange for menigheder,søndagskoler, ungdoms-og kvindeforeninger: firstemmig udsat for blandet kor/udgivet af Theo. S. Reimstad and M. Falk (Songbook: a new collection of spiritual songs for congregations, Sunday schools, youth, mission and women’s associations: arranged for mixed choirs/edited by S. Reimstad and M. Falk). Sangbogen was first published in 1897 in Minneapolis. Hymn #110 is “Stille, hvad ønsker du mer?” with music by Theodora Cormontan (uncredited). By the 1912 edition the hymn is still #110 but the title has been changed to “Høit fra det himmelste høie.” Previously the title of the hymn quoted the last line of each stanza of the text; now it quoted the first line of the first stanza, which roughly translates as “Loudly from the heavenly heights.” This is similar to the title in the current version of the Church of Norway hymnal–“Høgt frå den himmelske klåre.” I believe this is a Nynorsk version of the text written by Anders Hovden in 1925.

This hymn can also be found in “Koraler for korps,” 141 hymns and songs arranged for instruments by Edward B. Nilsen. In this edition the hymn is titled “Høit fra det himmelske høie.” There is also an SSA version arranged by Elling Enger. In this edition the piece is titled “Høyt fra det himmelske høye.” Its catalog number is CON7051, published by Cantando Musikkforlag.

The hymn also appears in the Protestant Madagascar Hymnal (2001), published by the Malagasy Lutheran Church Printing Office. The title of the hymn in Malagasy is “Any an-danitra am bony” (translated as “Up in heaven”). The hymn is attributed to “J. Commontan.”

This Cormontan hymn tune is also associated with the hymn “Ja, du har sagt at du kommer” [“Yes, you have said you are coming”], with a text by Jens Marius Giverholt [1848-1916]. It appears as number 873 in Sangboken [Songbook] (1983), published by the Norwegian Missionary Society, and number 717 in Ære være Gud[Honor of God] (1984), the hymnal for the Evangelical Lutheran Free Church (founded by Giverholt), published in Oslo.

The performance of “Høgt frå den himmelske klåre” continues to be noted in Norwegian newspapers. The December 9, 1960 edition of the Lillesands-Posten notes a song service entitled “We sing Christmas In” where the hymn is sung by the Justøy Womens’ choir. The hymn appears to be sung frequently at funerals and memorial services, usually without identifying the composer. In these cases, they may be singing the Cormontan hymn or they may be singing the Johan H. Grimstad setting of the text.

(above) A picture of the Cormontan hymn in the Norwegian Hymnal.

The following two edited entries come from Norwegian-American Historical Association publications:

From “A Singing Church” by Paul Maurice Glasoe (NAHA Volume XIII: page 92)

. . .There were numerous contributors who enriched the choir literature with single compositions or larger groups, now and then with a collection of hymns or songs. The Holter Publishing Company did a very worthy service by publishing singable music as a regular department of Ungdommens ven, later the Friend. All this material was collected and issued in several volumes under the name Frydetoner (Songs of Joy). The bulk of the work done up to 1900 was in the Norwegian language. Now and then a small contribution was made in English.

From “Music for Youth in an Emerging Church” by Gerhard M. Cartford (NAHA Volume 22: page 162)

The Norwegian Americans, like Lutherans everywhere, set a high value on the function of music in the life of the church. Sunday morning worship in the nineteenth century consisted, apart from the sermon, mainly of congregational singing. Musical emphasis, consequently, was almost exclusively on hymns, and pastors deplored the quality of the singing and exhorted the people to do better. From time to time, articles appeared in the church press on the subject of kirkesangen (singing in the church) and how it might be improved. The number of church hymnals in regular use was about as great as the number of Lutheran synods.

Worship services were conducted in Norwegian, and the standard hymnals were Landstad’s Salmebog, which had been authorized for general use in the United Church and in Hauge’s Synod, and the hymnal published expressly for the Norwegian Synod, which was commonly known as Synodens salmebog. In addition, a few congregations still used Guldberg’s Salmebog. These books, although generally satisfying to the older people, failed to meet the needs of the young, who thought the Lutheran hymns stodgy and uninteresting and who, furthermore, were becoming bilingual and wanted to sing hymns in English as well as in Norwegian.

From 1878 until 1914 a proliferation of books appeared containing songs designed to express Christian beliefs and aspirations in a less formal way than did the congregational hymnal. Many were issued specifically for young people. Most of the older Lutheran hymns dealt with doctrines fundamental to the faith. These the people were accustomed to singing in church, and many were dear to them. But toward the end of the nineteenth century there was an insistent demand for a new type of expression. It sprang from religious revivals, which emphasized individual experience as essential to Christian faith.

These songbooks, though widely used, met with serious opposition. In a typically forthright statement, the Norwegian Synod passed a resolution in 1896 which read, “Books such as Harpen, by Hoyme and Lund, and Frydetoner, by B.B. Haugan, ought not to be distributed by the Lutheran Publishing House in Decorah.” In 1901 the United Church also passed a resolution, but mentioned no names. It read, “The assembled delegates deplore the fact that there are congregations in our synod that prefer ‘gospel hymns’ to our Lutheran church music, because most of the so-called ‘gospel hymns’ are not suited either musically or textually for use in Lutheran services or Sunday schools. The delegates see it as the duty of the Sunday schools to teach the children to sing the congregational hymns and to take part in the service. Therefore, they hold that the contents of congregational and Sunday school hymns should be of a similar nature.”

It is interesting to note that Cormontan’s hymns were published by ministers from the Hauge Synod, while at that time the Cormontan family worshiped in a Norwegian Synod church, the synod that would most closely reflect the perspective of the Church or Norway. Theodora’s father had been a clergyman in the Church of Norway and lived until 1893.

It would appear that opposition to the Frydetoner hampered the dissemination of Theodora’s hymns. With the unification of the Norwegian, Hauge, and United synods in 1917 hymns in Norwegian, already fading from favor with the ascendency of the use of English, fell into disuse as new hymnals emerged to serve the unified synods.

Biographies:

Bernt B. Haugan (1862-1931) was an American Lutheran minister, politician, and temperance leader. Haugan had emigrated from Norway as a child and was educated in the United States. He attended Red Wing Seminary in Red Wing, Minnesota, the educational center and preparatory school of the Hauge Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. Haugan was ordained a Lutheran minister and served out his pastorate within the Hauge Synod. Members of the Hauge Synod were a group of Norwegian-American Lutherans who followed the principles of revivalist Norwegian lay preacher Hans Nielsen Hauge. In 1900, Haugan ran for the office of Governor of Minnesota as a candidate for the Prohibition Party. From 1904 to 1907 Haugan was co-owner and publisher for the Norwegian language newspaper Vot tid which was published in Minneapolis. Haugan wrote and published several Norwegian language prayer books. His most notable work was a hymnal entitled Vægterrøsten. Additionally, Haugan published a volume of temperance songs in a book entitled Kamp melodier (“Battle Melodies”).

Nils Nilsen Ronning (also Nils Nilsen Rønning) (May 19, 1870-June 25, 1962) was an American author, journalist and editor. Ronning was born in Bø in Telemark, Norway. After he immigrated to America in 1887 he studied for the Lutheran ministry and attended the Haugean Lutheran Red Wing Seminary from 1887-1892. He graduated from the University of Minnesota in 1892-96 (BA, MA). Ronning was a journalist and publisher associated with several newspapers and magazines published in Minneapolis, including Ungdommens Ven. As an author, Ronning was a prolific writer whose work appeared in both Norwegian and English. His writing includes several books, a group of short stories, popular travel narratives, and popular religious literature.

Melchior Falk Gjertsen (born February 19, 1847 in Kaupanger, Norway; died April 22, 1913 in Minneapolis, MN) was a Norwegian-American pastor, hymn writer, and school director. He worked as a priest in the Trinity Lutheran Church in Minneapolis, and was also director of education in the city.

Theodor Reimestad (born April 28, 1858 in Stavanger, Norway; died 1920) graduated from Augsburg Seminary in Minneapolis, where he later became a professor of Norwegian and Danish literature and Latin. Reimestad published “Kamp melodier” in 1892 with B.B. Haugan, one of the co-authors of Ungdommens Ven and Frydetoner.

The following is from “Fifty years in America” by N.N. Rønning–pages 80-82. Published by the Friend Publishing Co., copyright 1938. Reissued by the Library of Congress: Library of Congress Fifty years in America https://memory.loc.gov/service/gdc/lhbum/08330/08330.pdf

“The young people’s paper, Ungdommens Ven, had been in existence between six and seven years when I began to work for its publisher, K.C. Holter. There was never a widespread demand for a literary magazine among the Norwegians in America. While religious, social, literary and political questions kept the people of Norway at white heat, their brethren in America were chiefly concerned with making a living. Toward the close of the eighties, a new era was being ushered in. The church strife had spent its force and the question of uniting several church bodies was being discussed. The temperance movement and young people’s movement were under way. Choirs were being organized and men and women wrote poetry. A new generation was coming upon the stage, a generation with new interests and wider horizon. It was at that time Ungdommens Ven appeared. It came when the time was ripe for it, as an exponent of what was stirring in the minds and hearts of the more forward-looking people of Norse descent. It was three pastors who established Ungdommens Ven: B.B. Haugan, Lars Heiberg and K.C. Holter. They belonged to the more progressive wing of the Hauge’s Synod, and were among the leaders in the new movements.

Mr. P.R. Anderson of Bardo, Alberta, Canada, writes me that B.B. Haugan, while a student at Red Wing Seminary, 1879-1886, was talking about the need of a Norwegian young people’s paper. The first issue, published in March, 1890, bears the name of L. Heiberg, editor; B.B. Haugan, secretary and treasurer. The August issue, the same year, bears the names B.B. Haugan, editor, and K.C. Holter, publisher. Holter however, had taken care of the printing of the publication from the very first number. L. Heiberg was a brilliant writer and an eloquent speaker. B.B. Haugan struck a new note in Norwegian-American Journalism. He was a man of high ideals, deep sentiments and a most delicious humor. Few men could more easily move people to laughter or tears as B.B. His style was marked by fluency and simplicity. His writing in prose and poetry was like a fresh breeze from the mountains on a sultry summer day. But the man who furnished the stability, the perseverance and the untiring application to the task was K.C. Holter. Mr. [Mrs.?] Holter soon began to write poems and sketches for Ungdommens Ven which very highly appreciated. Before very long she did most of the literary work, Holter furnishing timely articles. The name of the publication was changed in 1916 to Familiens Magasin, which was discontinued in 1928. The Friend was started January, 1924. During the years 1918 and 1919 Mr. Herman E. Jorgensen was associate editor of Familiens Magasin and the North Star. He is an unusually brilliant man who commands an excellent style. Later he served as president of Red Wing Seminary and still later entered the ministry. In the spring of 1939 he takes over the position of editor of Lutheraneren In connection with Ungdommens Ven, Familiens Magasin and The Friend there have been published in all 40 titles with more than 200,000 copies.

I hasten to state that the first 20 titles owe their existence to the initiative and energy of K.C. Holter. He laid the foundation; I built on that foundation. Among the books published when Holter was the manager must be mentioned Frydetoner, volumes, I, II, III and IV, containing music and text for mixed choirs, 60,000 copies were sold of Frydetoner. This book met the demand of the large number of church choirs which sprang into being. It contained music by Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, German, American and Scandinavian composers. B.B. Haugan started Frydetoner I. The other volumes were published with the cooperation of Haugan, A.L. Skoog, Theodors Reimstad and others. Besides the four volumns of “Frydetoner,” there were printed the following music books: “Ekko fra Norden,” “Fram,” “Korsangeren,” totaling 10,000 copies.”